The Methane Wars: Part II

Regenerative doubts

Regenerative agriculture and livestock projects are being proposed by agribusiness leaders as a climate solution in South America, but behind the promises lie serious questions about deforestation, methane emissions, and greenwashing.

- Reporting and research: Maximiliano Manzoni - 2025 Bertha Challenge Fellow

- Editing: Paula Diaz Levi & Francisco Parra

- Maps: Tania Karo Mesa Montórfano

- Photos: Nicolás Granada

In March 2023, a pilot project using NASA satellites revealed the first inventory from space of carbon emissions and capture in 100 countries.

Using a map, it was possible to see for the first time an analysis of greenhouse gases calculated from space, rather than from the ground.

But what should have been a celebrated scientific breakthrough was used in a disinformation campaign promoted by agribusiness in South America. The Unión de Gremios de la Producción in Paraguay and the Instituto de Promoción de la Carne Vacuna Argentina used the NASA study to promote the idea that countries were “carbon positive” and that the impact of livestock farming on climate change was “a myth.”

This was a lie. Brendan Byrne, one of the scientists behind the NASA study, was clear when asked by email: the study only analyzed carbon dioxide and not methane, “which is a significant part of emissions from the livestock industry.”

The official denial did not prevent Norman Breuer, then representative of the agricultural sector to Paraguay’s National Climate Change Commission, and the Argentine government’s office to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, from using the NASA study to promote the idea that “carbon capture in pastures” offsets the impact of cows.

Breuer even used the event to push a similar agenda: changing how methane produced by livestock is calculated.

It is part of what is known as “regenerative” agriculture or livestock farming. It is a concept without a precise definition, which can incorporate everything from agroecology principles to grazing practices. But that does not prevent agribusiness giants such as Cargill and JBS, as well as organizations such as the Savory Institute and Frank Mitloehner’s CLEAR Center, from promoting it in countries such as Paraguay, Uruguay, Argentina, and Brazil, even for projects that have already been approved to sell carbon credits.

Interviews with scientists, field visits, satellite analyses, and documents reveal contradictions and questions surrounding these projects.

In Brazil, another regenerative agriculture and livestock project cleared native forest less than 10 years ago to start its production.

In Paraguay, a regenerative livestock project for carbon credits acknowledges that it will increase methane emissions in the short term under the promise of carbon capture in the medium term.

Scientists and experts warn of the risk that these temporary carbon captures will be used to “compensate” for pollution that will remain in the atmosphere for hundreds of years.

They also warn that large corporations such as Cargill, Syngenta, Bayer and South American countries are using labels such as “regenerative” practices to evade their climate responsibility.

There is also concern about the interest of major polluters such as Chevron—which financed the startup behind another project in Paraguay—and Vista Energy, which seeks to offset its impact from gas extraction in Vaca Muerta with regenerative livestock farming.

What is regenerative agriculture and livestock farming? It depends on who you ask.

Over the past 20 years, 55 million hectares of South America’s five main ecosystems have been devoured by fire, chainsaws, and bulldozers, largely to make way for the cattle industry. This has been achieved either through the 300 million cows grazing in the region or through commodity plantations such as soybeans, whose grains feed North American, European, and Chinese calves and pigs.

As a result of deforestation, the use of agrochemicals, and cow burps, the agricultural sector not only leads the way in contributing to emissions that worsen heat waves and floods in the region but also reduces the capacity of ecosystems and communities to cope with these extreme events.

It is the contradiction of a world that needs to tame the gases that are causing climate change while falling victim to its own greed at the same time.

Regenerative agriculture and livestock farming are proposed as solutions to ensure a sustainable food system.

Both are also the favorite words of large food corporations. A 2024 study analyzed the sustainability plans of 30 agribusiness giants and found that 80% of them, including Cargill, Nestlé, ADM, and even Coca-Cola, talk about “regenerative” practices. But only a third had clear objectives, and most did not explain how their plans would be implemented or whether they were just small pilot projects.

The study, conducted by the New Climate Institute, warned that the lack of a clear definition of regenerative agriculture and livestock farming opened the door to abuse through greenwashing.

It turns out that, depending on who you ask, regenerative agriculture has very different meanings.

For soil scientist and director of the Carbon Management and Sequestration Center at Ohio State University, Rattan Lal, the goal of regenerative agriculture is “to produce more with less: less land, less use of chemicals, less use of water, less greenhouse gas emissions, less risk of soil degradation.”

Lal, considered one of the leading scientific figures in the regenerative movement, proposes this as part of “The Green Revolution of the 21st Century.”

“Wasting food and polluting the environment are crimes against nature,” he asserts.

But behind these objectives lie several disagreements.

In the Netflix documentary Kiss the Ground, one of the most relevant pieces of publicity for regenerative agriculture, André Leu, director of Organics International, describes it in terms similar to agroecology. While they share some elements—such as the quest for more sustainable food production—this comparison is questioned for several reasons. Agroecology is not only a scientific discipline, but also a social and political movement that criticizes the very foundations of the food system, such as the use of pesticides and land grabbing.

Meanwhile, regenerative agriculture is being embraced by communities and small producers, but also by large corporations that the agroecological movement questions. One such corporation is Bayer, which claims that it needs pesticides such as glyphosate to carry out “no-till” farming practices, according to Rodrigo Santos, director of the multinational’s scientific division.

This is the same argument used by soybean associations in Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, and Paraguay to successfully lobby for the European Union’s approval of the pesticide’s use in 2023: “Glyphosate is a crucial tool in regenerative agriculture systems, where non-tillage and soil cover are a fundamental basis of a holistic approach that integrates technologies that help farmers produce more with less, promoting biodiversity, building resilience, and reducing the carbon footprint.”

This is contrary to the view held by Sarah Starman, from Friends of the Earth’s Food and Agriculture division: “Food corporations investing in regenerative agriculture must avoid greenwashing concepts such as no-till farming.”

The same applies to livestock farming. The term encompasses systems that combine crops or forest plantations with cows, those that graze cows on a rotational basis in the field or simply improve resource use and animal welfare through “holistic management.”

Despite the vagueness in the use of the term by large industries, most of their promises of “regenerative” agriculture and livestock farming point in the same direction: the possibility that agriculture and livestock farming could use the world’s oldest carbon capture technology, photosynthesis, to store carbon in the soil and thus offset their greenhouse gas emissions and even sell carbon credits.

South American agriculture has been promoting similar ideas at climate conferences for several years. At an event organized by the Interamerican Institute for Agricultural Cooperation (IICA) during COP27 in 2022, the then Minister of Agriculture of Uruguay, Fernando Mattos, held a press conference alongside Fernando Zelder, Secretary of Agriculture of Brazil, Ariel Martínez, Undersecretary of Agriculture of Argentina, and Santiago Bertoni, then Minister of Agriculture of Paraguay.

There, everyone affirmed that they had “a common position” in the face of “this whole narrative against our agriculture,” as Zelder said. “We are the only productive activity that captures carbon,” added Uruguayan Minister Mattos. “We are part of the solution, not the problem.”

According to a data analysis conducted for this research, in Paraguay, Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay alone, there are at least 66 projects that were promoted under the label of “regenerative” agriculture or livestock farming, either in progress or already registered to sell carbon credits.

Some were supported by corporations such as Cargill and Bayer, and others by a controversial organization: the Savory Institute.

At least three projects identified, two between Argentina, Paraguay, and Chile, and another in Brazil, have already been approved to sell carbon credits.

However, there are well-founded questions about the real possibility of regenerative projects compensating for their own impact and the legitimacy of selling credits.

Behind the carbon credits of regenerative livestock farming in Paraguay

It is the beginning of spring in Misiones, a department in southern Paraguay, on the border with Argentina. The sun is not yet merciless. The wind forces people to hold on to their hats. At the Las Talas ranch, some 35 technicians, businesspeople, and cattle ranch owners paid $150 for a day of training.

Las Talas is one of the cattle ranches certified for the sale of Verra carbon credits through the South American Regenerative Agriculture (SARA) project, managed by the Paraguayan company De Raíz.

Martín Mongelós, agricultural engineer and co-founder of De Raíz, defines regenerative livestock farming as “an improvement in the livestock business, at the expense of improving the biological capital and social capital” of the establishments that apply it. “For us, sustainability is not limited to being green or having forests, but the financial dimension is crucial. Today, the livestock sector is heavily indebted and, in some cases, financially unsustainable.”

Mongelós points out that with De Raíz, they seek to avoid “as far as possible” that “the only solution for greater productivity is deforestation.” The idea is simple in theory, according to the agricultural engineer: “Carbon capture in the soil is one of the measurable parameters and the only one for which an incentive is paid through carbon credits.” The cows graze in different places in a coordinated manner to allow “the pasture to grow, be consumed, and take root.”

The attendees listen to Alejandro Llano, a fifth-generation cattle rancher and one of the owners of Las Talas. Llano presents them with not only a proposal, but also a story. The story of how regenerative livestock farming led them to change their production model and their relationship with their cattle.

Like many livestock farmers in Paraguay, Llano was looking for a way to increase his profit margins in a sector that, despite its growth, is becoming less competitive compared to soybeans and forest plantations, partly due to the impact of extreme weather events exacerbated by climate change, of which they are both victims and perpetrators. This led him to opt for a “holistic management,” a way to reduce costs and increase productivity through rotational grazing.

“We thought we had found the solution. But we ran into the costs and challenges of implementation,” says Llano, describing what he defines as a moment when “the crisis became an opportunity,” using an apocryphal quote falsely attributed to Albert Einstein.

Thus, they joined the SARA program in conjunction with the company Ruuts and Ovi21, the Savory Institute’s “node” in Argentina.

The Savory Institute is a US organization that since 2012 has been promoting the idea of “regenerating the world’s pastures” through “coordinated work in developing countries” with governments and NGOs. According to official documents, in 2023 alone it received $3,958,901 in grants, donations, and member contributions. The organization’s financial data is not public, but it is known to be one of the beneficiaries of the “1% for the Planet” initiative, to which companies as diverse as the Oxxo mini-market chain, the Patagonia brewery, and the Flickr image bank contribute. It also receives funding through “Land to Market,” its “regenerative certification” services program, which includes carbon offsets that benefit companies such as White Oak and the food giant General Mills.

The institute owes its name and much of its fame to its founder, Allan Savory, an ecologist and rancher who was a colonial officer in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Savory is the creator of the “holistic management,” a concept adopted by De Raíz in Paraguay and Ovis21 in Argentina. In Uruguay, his work was highlighted by the Meat Institute (INAC).

At the entrance to Las Talas, several of Savory’s books are on sale. Llano says that “when Allan Savory came to Paraguay in 2022, he made it clear to me that the holistic management cannot be taught; it is something that depends on each field. This opened my eyes. As they say, when the student is ready, the teacher appears.”

During that visit in 2022, Savory shared the stage with Norman Breuer, the agribusiness representative to the National Climate Change Commission. The talks were organized by the Rural Association of Paraguay.

There, Savory falsely claimed that “science recognizes that climate change is not caused by livestock, oil, or coal (…), but by the way we manage them.” Savory described his concept of holistic management “as a vital discovery for humanity that continues to be treated as heresy by most institutions, just as the discoveries of Galileo and Copernicus were treated when we believed that the Earth was flat and the center of the universe.”

However, “this discovery has been spread by ranchers, scientists, and pastoralists,” he said.

Savory became famous for a TED talk in 2013 where he defended the controversial idea behind his “holistic management”: to reverse climate change, we need more cows, not fewer. Savory argued that under livestock grazing management methods, it would be possible to capture all the fossil fuel emissions that led to the current climate crisis and reverse desertification.

“It’s the only alternative for humanity.” The audience applauded his talk. But not everyone is so convinced.

Regenerative agriculture and livestock farming is being proposed by Big Ag as a solution to their impact on climate and biodiversity.

Most of the projects supported by corporations like Cargill or organizations like the Savory Institute are focused on carbon capture through the soil with no-till soy farming or rotational grazing of livestock.

But the science and our findings put into question these promises.

Projects with prior deforestation, more methane emissions, use of pesticides and doubts about the posibility itself of offseting their emissions with soil carbon-capture are some of the questions raised.

Permanence, methane, and deforestation: the problems beneath the soils of regenerative projects in South America

A letter responding to Savory’s 2013 talk, signed by American scientists specializing in soil and pastures, stated that “scientific evidence unmistakably demonstrates the inability of Mr Savory’s method to reverse rangeland degradation or climate change.”

The main concern about these projects has to do with the promise of carbon capture and storage in the soil. Specifically, the capacity and duration of that carbon storage.

As Gilles Dufrasne, a researcher specializing in carbon markets, explains in his study for the organization Carbon Market Watch, “ensuring that captured carbon will not be released back into the atmosphere is impossible to guarantee in land-based initiatives,” especially “due to changes in management practices or extreme weather events” such as frosts and droughts. This point is also highlighted in the renowned study “Grazed and Confused” conducted in 2017 by researchers from the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge, and Aberdeen, among others.

The study points out that there is evidence that grazing, trampling, and livestock manure can promote carbon capture by stimulating plant growth—which is responsible for photosynthesis. But the soil has a finite capacity. “Even under favorable conditions,” the research notes, «the soil captures carbon until it reaches equilibrium. After that, it cannot capture any more.»

Dufrasne is even more critical. “It is virtually impossible to ensure that enough carbon will remain in the soil to offset fossil fuel emissions, as that CO₂ will continue to affect global warming for several hundred years.”

When asked about this, Martín Mongelós from De Raíz points out that the process of capturing carbon in pastures “is a dynamic, short-cycle process, but one that is constantly being renewed.” The current contracts with ranch owners for the carbon project are for 10 years.

Scientific evidence suggests, however, that to neutralize the impact of fossil fuel emissions on climate change, any carbon capture would need to last for around 1,000 years.

The gap of hundreds of years between the life of fossil fuel pollution in the atmosphere and the contracts for projects to offset it is one of the reasons why a court in Germany forced Apple to remove the description “carbon neutral” from its smartwatches that used forest carbon credits from Paraguay.

The other problem is methane. Official documents from the regenerative livestock project for carbon credits promoted by Ovis21 and De Raíz in Paraguay admit that for it to work, more cows are needed, which will increase methane emissions. This was confirmed by Mongelós, who explained that in his view, “these emissions will be subtracted from the carbon capture from the soil.”

However, this calculation is disputed because “methane is not perfectly recycled,” as researcher Nicholas Carter pointed out in the previous report in this series. Fast and furious, it does not last long in the atmosphere but heats it much more than carbon dioxide. Even after it disappears, this warming affects the oceans for decades.

Mongelós’ statement also presents a dilemma: confirmed increases in methane under the promise of carbon capture in the medium term.

The methane dilemma also calls into question the proposal put forward by the Savory Institute, which states on its website that “a new methodology for estimating the impact of methane, known as GWP*, is becoming widely accepted and reduces the proportion of greenhouse gases related to livestock farming, although the academic debate on the exact figure continues.”

This metric, as we have already reported, is promoted by Frank Mitloehner, among others, an American researcher funded with millions of dollars from agribusiness through a foundation linked to Cargill, JBS, and Tyson Foods, among others. On his tour of South America, in addition to promoting the controversial metric that would allow the livestock industry to hide its climate impact, Mitloehner also claimed that methane belched by cows is recycled by pastures.

In fact, one of the recommendations in the confidential report for which he was paid $8,000 by the Uruguayan government included “considering carbon capture from grazing lands” in the livestock sector.

He is not alone. Gilberto Tomazoni, an executive at meat giant JBS, pointed out that “the current method of calculating emissions is flawed” and that he would attend the upcoming COP30 in Brazil to demonstrate that the country’s livestock industry is not harmful to the environment.

A study published in Nature in 2023 had already pointed out that “carbon capture is a benefit that is limited in time and that there are intrinsic differences between short-lived greenhouse gases—methane—and long-lived greenhouse gases—carbon dioxide,” so relying solely on carbon capture from grasslands to offset the impact of livestock systems is not possible.

![]()

Screenshot of the official document of the carbon project in Paraguay admitting that an increase in methane emissions is expected under the initiative. Source: Verra

Brazil: selling carbon credits on the same property where deforestation occurred

In addition to doubts about the possibility of regenerative livestock farming offsetting its own pollution, the proposal requires a lot of space to allow livestock to rotate between pastures.

While Paraguay’s carbon credit project excluded cattle ranches that had been deforested less than 10 years ago, this criterion, like the concept of regenerative cattle ranching itself, is not the same in all projects that sell carbon credits on Verra.

Landsat satellite imagery and independent analysis with Global Forest Watch and Mapbiomas show that another regenerative agriculture and livestock scheme in Mato Grosso, Brazil, carried out deforestation between 2015 and 2018.

The project is being promoted by NaturAll Carbon, an Anglo-Brazilian company founded by a former Petrobras official, which obtained Verra approval in June 2025. The project proposes a combination of carbon capture with soybean crops—which will use pesticides—and rotational grazing.

In its official documentation to achieve Verra verification, the project denied the deforestation of native ecosystems.

When consulted about this issue for this report via email, NaturAll confirmed the deforestation but responded that most of the cleared areas “are outside the project’s carbon credit area,” although they are within the same ranch. In the same communication, the certifying company undermined the veracity of the deforestation alerts identified by Global Forest Watch and Mapbiomas—the latter having been used by them to register in the carbon markets, defending their due diligence process with “satellite images and field visits.”

They also point out that in the only exception, their own analysis concluded that it was a “false positive.” “Cattle ranchers often leave isolated trees or small groups of trees to provide shade for their livestock, but these features do not represent native ecosystems,” the email states.

The “false positive” described by NaturAll does not refer to deforestation identified by satellite imagery within the area that does sell regenerative carbon credits according to its own documents. NaturAll did not respond to these findings.

The deforestation from this project can also be seen in our interactive map of regenerative schemes for carbon credits in Paraguay, Uruguay, Brazil and Argentina.

In the case of additional deforestation on the property, the case illustrates the absurdity of some regenerative projects in carbon market methodologies, where the same ranch can clear forests and at the same time sell carbon credits from soybean plantations and livestock farming. This is known as “carbon leakage”: when the activity to capture emissions inadvertently generates more emissions elsewhere.

This type of situation has led even organizations that believe in regenerative agriculture, such as the European Climate Farmers, to take a stand against the current approach to carbon credits.

According to a letter shared by Climate Farmers in response to inquiries about why they abandoned regenerative carbon credits, “the current carbon market inadvertently supports large-scale industrial agricultural operations, thereby reinforcing existing inequalities and eroding the socioeconomic and ecological diversity that is vital for a truly regenerative future.”

Oil companies, agribusiness giants, and climate change deniers position regenerative agriculture in the region and at COP30

Cargill and the Land Innovation Fund

Cargill and the Land Innovation Fund

Since 2022, it has provided funding to the Argentine Association of No-Till Farmers (Aapresid), the Youngas Foundation (Argentina), and the Moisés Bertoni Foundation (Paraguay) to conduct pilot analyses of potential carbon credit projects involving soybeans and livestock in the Argentine and Paraguayan Chaco.

However, greenhouse gas emissions data from Climate Trace show that at least two of these sites, in the Paraguayan Chaco, were deforested less than 10 years before the project began in 2017.

NaturAll

NaturAll

Where our investigation identified deforestation within the area that is now being sold for carbon credits.

Savory Institute

Savory Institute

Advises companies behind the SARA regenerative livestock project in Paraguay and Argentina. Also another independent project in Uruguay.

Boomitra with funds from Chevron and Yara International

Boomitra with funds from Chevron and Yara International

One of its projects in Paraguay will be used by Singapore to meet its new climate commitments under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

Vista Energy in Vaca Muerta

Vista Energy in Vaca Muerta

According to its 2024 sustainability report, it seeks to offset emissions from gas extraction in Vaca Muerta with regenerative livestock farming projects.

Interviewed for this piece, Silvia Calderón, director for Latin America at the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), explains that much of the boom in carbon projects in the region, specifically in agriculture, is due to the fact that “there is a great need for mitigation finance.”

According to the expert, imbalances occur because “in our region, the Ministries of Environment are small, so the private sector moves faster. The region has been positioning itself in conservation projects, and the upcoming COP30 in Belem will be key.” Calderón admits that the permanence of regenerative agriculture projects “is one of the essential elements.” In 2024, the SEI warned in a report that without clear rules on the matter, “carbon credit programs may not adequately reflect reduced emissions, contributing to greenwashing.”

Despite the contradictions and questions, an analysis carried out for this investigation shows that in Paraguay, Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay alone, there are at least 66 carbon credit projects in various stages of development under the banner of “regenerative” agriculture or livestock farming.

During COP30, the host country will have at least 33 panels on agriculture and livestock in its so-called “Agrizone,” the pavilion of the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA), the same public-private entity that promotes the adoption of GWP* in the country as a way to measure methane from livestock. Among the companies that will be represented on these panels are Nestlé, Pepsico, and others such as Cargill, Bayer, ADM, BASF, Syngenta, Bunge, and Cofco, as well as oil companies Chevron and BP, organized around the World Business Council for Sustainable Development. Since COP28 in Dubai in 2023, this organization has been sponsoring the “Regenerative Landscapes” initiative in conjunction with the governments of the United Arab Emirates and the United States. The main objective of the initiative is to increase funding for so-called regenerative projects.

The Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA) will also be present in the same pavilion. In September 2025, IICA signed an agreement with Boomitra, a company that seeks to promote regenerative agriculture carbon projects. Boomitra aims to develop these projects in countries such as Argentina and Paraguay, and in its early stages received funding from investment funds such as Chevron.

In addition to Boomitra, the Savory Institute, and NaturAll, another promoter of regenerative agriculture projects for carbon credits is Vista Energy, an oil company that exploits gas fields in Vaca Muerta, Argentina, and is investing in regenerative agriculture to offset its emissions. There is also Cargill, through its Land Innovation Fund, which has provided more than $30 million in funding to organizations such as Fundación Solidaridad and Fundación Moisés Bertoni for “pilot studies” in the Paraguayan and Argentine Chaco and the Brazilian Cerrado. In the case of Solidaridad, it also used funding from the Dutch government to pay Norman Breuer—yes, the same person who used a NASA study to lie about livestock farming and influenced the country’s methane policies—to have the pro-agribusiness researcher conduct a study on emissions from the sector on selected ranches in the Paraguayan Chaco.

According to Breuer’s findings, out of 10 cattle ranches, six proved to be “carbon negative.”

Breuer’s report was presented in 2025 by the Rural Association of Paraguay for use by the country’s foreign ministry to “demystify arguments.”

But the report itself, prepared by Breuer and accessed for this investigation, reveals the fine print. His analysis did not consider emissions from deforestation carried out for livestock activities.

Vista Energy corporate report on how they will use regenerative projects to offset their Vaca Muerta oil emissions

The Paraguayan government is moving forward with its new climate plans, including regenerative agriculture through “no till farming» among its measures to meet its commitments under the Paris Agreement, in a move that was celebrated by agribusiness representatives as a victory compared to previous commitments made by the country.

Among the entities that were part of the process is the Paraguayan Federation of Direct Seeding, which maintains that “soybeans capture more carbon than forests” and is represented by Albrecht Glatzle—the same person who secured the inclusion of GWP* in the country’s latest communication to the United Nations on climate. And the new president of the Federation is none other than the former president of the Sustainable Beef Board: Alfred Fast.

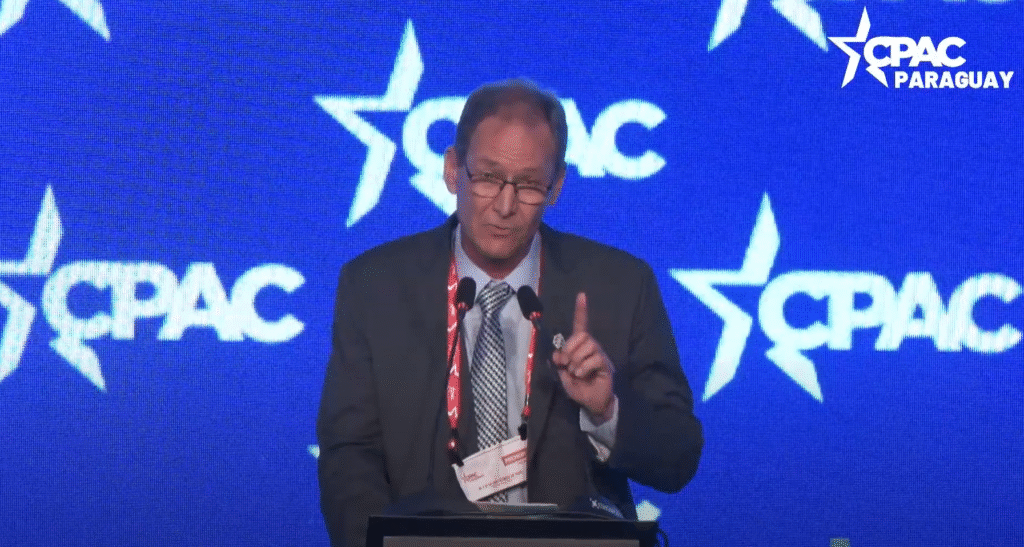

Both Glatzle and Fast influence and participate in climate policies that favor agribusiness despite their positions and links to climate change denial. Glatzle remains linked to CLINTEL, the European organization that denies the climate crisis, while Fast participated in September 2025 representing the Association in a speech during the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) event in Asunción—one of the main organizations that aligns with the international far right. It was in the same room at the Sheraton Hotel in Asunción where, three years earlier, Frank Mitloehner presented Fast and Glatzle, among others, with the possibility of changing how the impact of livestock farming on the climate was calculated.

At the CPAC event, Fast declared that environmentalism is “the perfect excuse to attack civilization.”

“Is the current climate change something out of the ordinary? The answer is no,” said Fast, who erroneously claimed that thanks to greenhouse gas emissions—such as those from fossil fuels and livestock— “agricultural crops grow better.”

Before him, Argentina’s libertarian president Javier Milei took the stage. The event in Asunción concluded with a speech by Paraguayan president Santiago Peña. Both governments will negotiate agricultural issues with Brazil and Uruguay at the upcoming COP30.

A few months before the conference begins, the interest shown by livestock farmers in what Llano, Mongelós, and other enthusiasts of regenerative agriculture have to say and teach suggests that, beyond the questions, the topic is here to stay.

The doubt and the debt of regenerative promises lie in the ability to transfer a particular case to a reality as diverse as the ecosystems where millions of cows graze in South America.

Answers may lie beneath these soils. The question is whether agribusiness wants to hear them.